Keeping up appearances: it’s all about the windows

Gillian Livingstone looks at the latest thinking on how a building’s energy efficiency can be improved without compromising its appearance

In October 1981 Alec Clifton-Taylor presented an episode of the BBC TV series, Six More English Towns, from Bradford on Avon. The pace of the programmes is considered; his delivery is deliberate. He is charmed by the picturesque setting of the town, its varied history, the wealth of architectural detail. He admires the Venetian windows and the Ionic pilasters in the Georgian façade of Church House (built in 1732) and notes how the arches over the first floor windows give them a ‘quizzical air’.

But all is not well. Too many glazing bars in the sash windows so characteristic of Georgian architecture are missing. He explains sadly how they had been sacrificed because the Victorian owners liked an uninterrupted view of their gardens. The modification results in a window that consists of two rectangles: an aberration beside those buildings that have escaped renovation. That Westbury House and houses on Kingston Road have restored their bars is a reassuring resurrection of a previous era.

The programme (which can be found on YouTube) is a reminder of how improvements can enhance or undermine the appeal of a building, according to the architectural and aesthetic context. For example, the square window shapes of 17th and 18th century weavers’ cottages are appropriate to the low-ceilinged rooms, whereas the longer rectangular windows match the proportions of the taller rooms of the Georgian period.

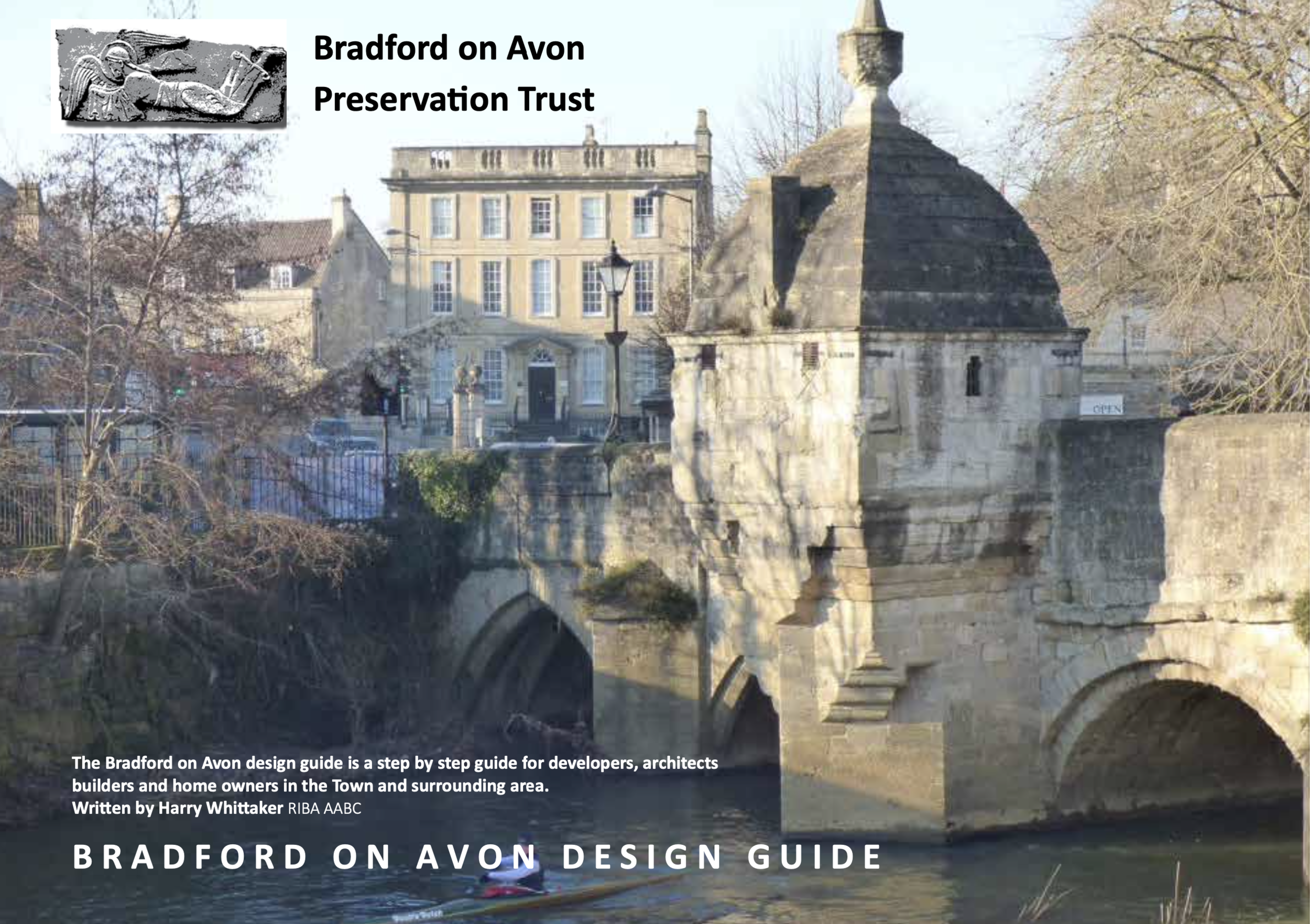

The detail above comes from the Bradford on Avon Design Guide, written by conservation architect Harry Whittaker for developers, architects, builders and homeowners in the town and surrounding area. Its aim – to encourage ‘best practice by any party capable of degrading the town’s ambience’ – chimes with Clifton-Taylor’s concerns around preserving the historic character and architectural features of the town.

The section on Windows explains how, until the end of the 17th century, fenestration in Bradford on Avon was mostly mullioned and transomed casements with leaded glass. These began to be replaced around 1685 by vertical sliding sash windows with heavy weights made of lead or cast iron, housed in sash boxes which were exposed to the elements. After the devastation of the Great Fire of London, the 18th century saw a series of Acts passed to address the risk of combustible building materials. The Act of 1774 decreed that windows should be recessed by a minimum of 4 inches and their frame should be rebated behind the masonry, a feature that can be seen in Georgian housing in Bradford.

Recent planning applications have reflected concerns about energy efficiency and noise reduction, as many of these historic buildings are difficult to heat and are situated on busy roads.

By the early 19th century, the chunky glazing bars were giving way to thinner version as manufacturers became skilled in the detailed joinery needed to retain the glass.

The windows were still subdivided into smaller panes and glazed with crown glass, a type of hand-blown glass once prevalent in Bradford on Avon, but now increasingly rare. The molten glass was blown into a balloon shape and spun round a central rod to create a disc with characteristic circular lines. These irregularities refract the light to produce interesting effects and any window pane with crown glass should be preserved as a distinctive feature and not replaced.

Some of the late Georgian/early 19th century buildings display a simpler version of sash windows without sash boxes and weights. Instead, the upper sash is held in place by a hinged bracket stay which is released to allow the window to open. Other windows lack a lower timber cill and sit directly on the stone below.

The guide is aimed at homeowners who enjoy the privilege of living in a period property and who embrace both the benefits and responsibilities. The first and best course of action is to retain and repair rather than replace, but where replacement becomes necessary, the guide recommends using local materials and following historic methods of construction. Any improvements should be in proportion to the size and scale of the property and there should be visual harmony with nearby window types and their design. Double glazing has been deemed inappropriate for the reglazing of historic buildings, mainly because the rebate of casements and sash windows is too narrow (as discussed above).

Recent planning applications have reflected concerns about energy efficiency and noise reduction, as many of these historic buildings are difficult to heat and are situated on busy roads. A recent publication from Historic England, Adapting Historic Buildings for Energy and Carbon Efficiency Historic England Advice Note 18 (HEAN 18), warns that ‘buildings remain the UK’s highest carbon emitting sector’ but emphasises the part historic buildings can play in the transition to a Net Zero society: ‘The most sustainable building is one that already exists’ because of their continued repair and maintenance, and their construction in local, naturally resourced and low carbon materials.

The advice on windows recommends draught-proofing and secondary glazing, and – in a change to previous advice – double glazing. A property in Church Street (pictured above) is a good example of secondary glazing, and the owners’ experience is worth sharing.

The improvements were carried out by Mitchell & Dickenson who specialise in a lightweight hi-tech substitute to glass developed in the aeronautical industry. The windows can open as before without extra frames, and being fitted with magnetic tape can be removed easily. This and the fact the secondary layer is invisible from the outside places the improvement in the ‘permitted development’ category and under the new guidance would be unlikely to require planning permission. The company claims the system is highly energy efficient, reducing heat loss by 70 per cent; the insulating properties can halve noise levels.

Feedback from the property owners a year after the installation is positive. Fluctuations in energy prices make it difficult to assess any effect on energy costs, but they found that, after early spring, they rarely used their heating system. Condensation around the window frame was reduced considerably, and as a result there was much less need to redecorate. The installation was a serious investment but the long-term benefits were clear.

It is significant that Historic England have changed their position on double glazing, which they now consider ‘generally acceptable.’ They recommend slim-profile or vacuum double-glazing to be retained within the original glazing bars. To gain the full benefit of the modification the windows should be refurbished and draught proofed.

There are some exceptions where the glazing bars are narrow or the glass is of historic interest, and in most instances, planning permission would need to be applied for. If the windows are a modern replacement, and a sympathetic reconstruction, planning permission is not required. Knowledge of the history of your property and any modifications is very helpful here.

A webinar organised by Bath & North East Somerset Council (B&NES) in partnership with Bath Preservation Trust and Bath & West Community Energy (BWCE) assessed the advantages of double glazing. A single pane window will experience high levels of heat loss: for example, at an outside temperature of 5° and an inside temperature of 20°, the pane will register 2°. In a case study the slim double glazing reduced the loss by half, but the owner did have to modify the glazing bars, which was only possible because the original windows had been replaced in the 1970s. He also reported that the noise levels outside had been greatly reduced.

Building improvements are clearly a balancing act between preserving the past and enhancing the present, an ever-changing dynamic of keeping the integrity of a historic building while keeping it relevant. After all we live in a home, not a museum. Windows reflect this liminality: outside, an observer will see respect for the enduring character of a historic building; inside a warm, welcoming living space.